Quite often fast databases, super-duper backend caching layers and other fancy stuff doesn’t help if you don’t serve your customer right. Take, for example, Twitter. This service has lots and lots of clicks, people following each other, in endless loops, trees, and probably serving occasional page-views.

I noticed that every click seemed to be somewhat sluggish, and started looking at it (sometimes this gets me free lunch or so ;-)

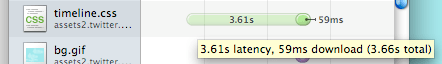

Indeed, every click seemed to reload quite a bit of static content (like CSS and JavaScript from their ‘assets’ service). Every pageview carrying information took 2s to serve, but static content slowed down the actual page presentation for three-six additional seconds.

Now, I can’t say Twitter didn’t try to optimize this. Their images are loaded from S3 and have decent caching (even though datacenter is far away from Europe), but something they completely control and own, and what should make least amount of costs, ends up the major slow-down.

What did they do right? They put timestamp markers into URLs for all included javascript and stylesheet files, so it is really easy to switch to new files (as those URLs are all dynamically generated by their application for every pageview).

What did they do wrong? Let’s look at the response headers for the slow content:

Accept-Ranges:bytes

Cache-Control:max-age=315360000

Connection:close

Content-Encoding:gzip

Content-Length:2385

Content-Type:text/css

Date:Wed, 25 Mar 2009 21:12:21 GMT

Expires:Sat, 23 Mar 2019 21:12:21 GMT

Last-Modified:Tue, 24 Mar 2009 21:21:04 GMT

Server:Apache

Vary:Accept-Encoding

It probably looks perfectly valid (expires in ten years, cache control existing), but…

- Cache-Control simply forgot to say this is “public” data.

- ETag header could help too, especially if no ‘public’ is specified.

- Update: Different pages have different timestamp values for included files – so all caching headers don’t have much purpose ;-)

And of course, if those files were any closer to Europe (now they seem to go long long way to San Jose, California), I’d forgive lack of keep-alive. Just serve those few files off a CDN, dammit.